If you are starting to learn Japanese, you will quickly encounter three different types of characters: hiragana, katakana, and kanji. Unlike languages that use a single alphabet, the Japanese language uses all three scripts together in writing. This can be confusing at first, but each script has a specific role. Hiragana and katakana are phonetic syllabaries (each character represents a sound), whereas kanji are characters of Chinese origin that represent meanings. This article will explain katakana vs hiragana vs kanji – what each of these writing systems is, how they differ, and when to use each one.

1. Hiragana

Hiragana is one of the core components of the Japanese writing system. In the Japanese language, hiragana is a set of symbols that represent all the basic syllable sounds. There are 46 basic hiragana characters , which cover every sound in Japanese. Each hiragana character corresponds to a syllable such as あ (a), い (i), う (u), etc. (plus one standalone consonant ん (n)). These characters do not carry meaning by themselves; they purely represent pronunciation.

Usage of Hiragana

Hiragana is primarily used for native Japanese words and grammatical elements. In modern Japanese text, hiragana characters serve several important functions. They are used when writing verb and adjective endings, grammatical particles, and other function words, as well as for words that do not have a corresponding kanji (or when the kanji is obscure). For example, the sentence-ending copula です (desu) or particles like は (wa) and を (o) are written in hiragana. Hiragana also appears as okurigana, the phonetic endings attached to kanji characters to indicate verb conjugations and adjective inflections.

Hiragana can be used to write entire words that could technically be written in kanji, especially in materials for children or beginners. In fact, Japanese children’s books are often written mostly in hiragana, because young learners have not yet learned many kanji. However, writing everything in hiragana is not common in adult-level text because it becomes difficult to read without the visual cues that kanji provide. Japanese is written with no spaces between words, so a combination of kanji and kana helps distinguish word boundaries in a sentence. In other words, mixing kanji and hiragana (along with katakana where appropriate) makes written Japanese much easier to scan and understand.

One common question for beginners is kanji vs hiragana – why have two different scripts for writing? The main difference is that kanji characters have inherent meanings and usually represent content words (nouns, verb roots, etc.), while hiragana characters represent sounds and serve grammatical functions. In a typical sentence, the core vocabulary words will be in kanji, but the grammatical endings and particles around them will be in hiragana. This combination allows Japanese text to convey meaning efficiently (through kanji) while still indicating grammar and pronunciation (through hiragana).

How Many Hiragana Are There?

So, how many hiragana are there in total? Modern hiragana consists of 46 characters. This set is often displayed in a chart called the gojūon (“50 sounds”) table. Historically there were additional kana symbols (now obsolete), but today’s Japanese uses 46 fundamental hiragana symbols to cover every native sound syllable. By learning these 46 hiragana, a student can phonetically write anything in Japanese. Mastering hiragana is typically the first step in learning Japanese, since it provides the foundation for reading and writing.

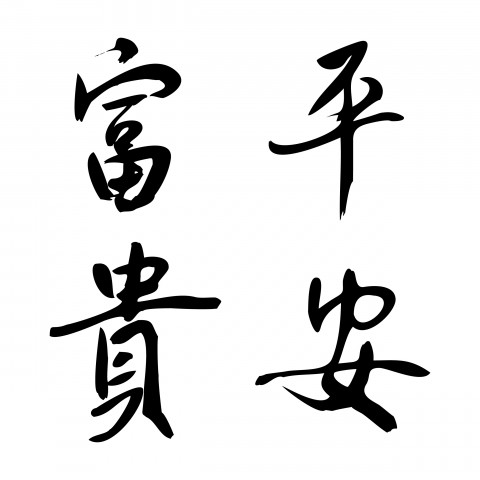

(Fun fact: The word “hiragana” itself can be written in kanji as 平仮名, which literally means “ordinary” or “simple” kana. This name reflects that hiragana was considered the “standard” way to write Japanese phonetically.)

2. Katakana

Katakana is the second phonetic syllabary in Japanese. What is katakana in simple terms? Essentially, it’s a parallel set of characters to hiragana: each katakana symbol corresponds to the same set of syllable sounds, but katakana has a distinct angular appearance and is used for different purposes. Like hiragana, katakana also contains 46 basic characters. In other words, the sounds ka, ki, ku, ke, ko have one hiragana character (か, き, く, け, こ) and a corresponding katakana character (カ, キ, ク, ケ, コ), and so on. The difference lies not in pronunciation but in usage and visual style. Katakana characters are typically boxier and more geometric in shape, in contrast to hiragana’s soft, flowing curves.

Usage of Katakana

Katakana is used in specific situations in Japanese writing. Its primary role is to write foreign-origin words (gairaigo) and foreign names in Japanese. For instance, テレビ (terebi, “television”) and ロンドン (Rondon, “London”) are written in katakana, since these terms were borrowed from other languages. Katakana is also used for technical and scientific terms, the names of many plants and animals, and for onomatopoeic sound words, especially in manga or literature. Additionally, katakana can be used stylistically to give emphasis to a word – similar to how italics are used in English. For example, a restaurant menu might write コーヒー (kōhī, “coffee”) in katakana to make it stand out, even though coffee is an everyday word.

In summary, if a word is not originally Japanese (or if the writer wants to highlight it for effect), katakana is the script of choice. Most Western loanwords, modern terms, and imported names appear in katakana. On the other hand, everyday native Japanese words (like 食べる たべる taberu, “to eat”) are usually written in hiragana or kanji, not katakana.

Katakana vs Hiragana: It’s natural for beginners to wonder about the difference between these two kana. Essentially, hiragana vs katakana comes down to context rather than sound. Both scripts represent the exact same set of sounds (they are phonetic alphabets), but they are used in different contexts and have different looks. Hiragana is used for native Japanese words, grammatical elements, and inflections, whereas katakana is reserved for foreign words, loanwords, certain names, and for emphasis or stylistic purposes. Visually, hiragana characters are more cursive or rounded, whereas katakana characters have sharp, angular strokes. Despite these differences, the two sets of kana are parallel; any syllable that can be written in hiragana can also be written in katakana. For example, the sound “ko” is written as こ in hiragana and コ in katakana – same sound, different script.

Just like hiragana, katakana’s 46 symbols must be memorized by learners. Many katakana characters even resemble their hiragana counterparts in some way (for example, か vs カ for ka), but with simpler, straighter lines. Typically, one learns hiragana first and then katakana. Being comfortable with katakana is important for reading things like foreign names, imported terms in newspapers or websites, and items like labels or signage in Japan.

3. Kanji

Kanji are the logographic characters used in Japanese, originally adopted from Chinese. These are very different from kana. Instead of representing a syllable sound, a kanji character usually represents a whole concept or word (or part of a word). For example, 水 means “water,” 森 means “forest,” and 食 means “to eat.” Because kanji carry meaning, they allow Japanese writing to be concise – a single kanji can express what would take several letters or syllables in kana.

Usage of Kanji

Kanji are used for most content words in Japanese. In a typical sentence, the nouns, the stems of verbs, and the stems of adjectives are written in kanji. For instance, in 東京に行きます (Tōkyō ni ikimasu, “I will go to Tokyo”), the word 東京 (“Tokyo”) is written with kanji, and 行 is the kanji part of the verb 行きます (“to go”), while the ending -きます is written in hiragana. Using kanji conveys the core meaning of words and makes the sentence more compact and readable, whereas writing the entire sentence in hiragana (「とうきょうにいきます」) would be longer and harder to parse at a glance.

There are thousands of kanji in existence – it is often said there are over 50,000 kanji characters in total. However, only a fraction of these are used in daily life. The Japanese government maintains a list of 常用漢字 (Jōyō kanji), which includes 2,136 kanji deemed the most essential for literacy. These “regular-use kanji” are taught during compulsory education in Japan. In practice, knowing the ~2,000 Jōyō kanji (plus some additional characters for names and specialized terms) will enable you to read most newspapers, books, and signs. By contrast, hiragana and katakana each have only 46 symbols, which might make one wonder hiragana vs kanji: why not just use hiragana for everything? The reason is that kanji and hiragana serve different roles and actually complement each other.

Kanji characters carry specific meanings, which helps differentiate words that sound the same. Japanese has many homophones (words that share the same pronunciation but different meanings), and writing in kanji helps clarify which word is intended. For example, はし (hashi) can mean “bridge” (橋), “chopsticks” (箸), or “edge” (端) – all are pronounced hashi but written with different kanji. If you used only hiragana, all of these would be written as 「はし」, creating ambiguity. Kanji eliminate this confusion by providing a unique visual symbol for each meaning. Another aspect of hiragana vs kanji is efficiency: kanji allow information to be conveyed in a compact form. A sentence with kanji is typically shorter (in number of characters) and easier to visually navigate than the same sentence written entirely in hiragana. In essence, kanji are used for the content and clarity they provide, while hiragana ties the kanji together and fills in the grammatical details.

How to Read Kanji

Learning how to read kanji is one of the bigger challenges in Japanese. Unlike hiragana or katakana, which have exactly one reading for each character, a single kanji can have multiple pronunciations. This is because most kanji have at least two kinds of readings: the on-yomi (Chinese-derived reading) and the kun-yomi (native Japanese reading). Which reading is used depends on the word and context. For example, the kanji 日 (meaning “sun” or “day”) can be read as nichi in the word 日本 (Nihon, “Japan”), but as hi in 日曜日 (Nichiyōbi, “Sunday”). There are general patterns (for instance, kanji in compound words often use on-yomi, while a standalone kanji usually uses kun-yomi), but many exceptions exist. Therefore, memorizing vocabulary and reading practice are key to knowing the correct pronunciation of kanji in each context.

Because kanji can be hard to read for beginners, Japanese texts for children or language learners often include 振り仮名 (furigana) – small kana written above kanji to show the pronunciation. Furigana acts as a reading aid. For instance, a newspaper might put furigana on a rare or difficult kanji so that readers know how to pronounce it. If you come across an unfamiliar kanji while studying, you can use a dictionary or an app to find its reading. Some learners even use tools that convert kanji to hiragana (sometimes searched for as “kanji a hiragana”) – essentially providing furigana for every kanji in a text. In essence, furigana or such conversion tools rewrite the kanji in hiragana so you can read the text more easily. As you become more proficient, you will rely less on furigana and recognize the kanji and their readings on your own.

Katakana vs Kanji

Beginners might also wonder about katakana vs kanji – these two could not be more different. Katakana is a phonetic script (like hiragana) where each symbol represents a syllable and has no meaning by itself. Kanji, on the other hand, are logographic symbols that usually carry a meaning (and often correspond to whole words or concepts). The two scripts are used for different purposes in Japanese. You generally would not write a native Japanese word in katakana (unless for emphasis or style), and you would not invent a kanji for a foreign name. For example, the country name “France” is written フランス in katakana (Furansu), since it’s a foreign word. The word “person” is written 人 in kanji (hito or jin), carrying the meaning of a human being. Writing “person” in katakana (ヒト) or hiragana (ひと) is possible, but in normal Japanese text it would be highly unusual because the kanji 人 is the standard form. In modern Japanese, kanji and hiragana are mixed to write sentences (with katakana used when needed for specific terms). Kanji provides the content and meaning, while kana (hiragana/katakana) provide grammar, pronunciation, and foreign words – each script playing its part.

4. Conclusion

In summary, the Japanese writing system uses a combination of three scripts, each with a distinct role. Hiragana is the fundamental phonetic script for native words and grammatical elements, katakana is the phonetic script for foreign words, loanwords and special emphasis, and kanji are the thousands of characters that convey core meanings. A single Japanese sentence may incorporate all three together – for example, kanji for nouns and verb roots, hiragana for the grammatical endings and particles, and katakana for a borrowed name or sound effect.While it may seem daunting at first to learn three sets of characters, each one has its purpose and they complement each other. Start with hiragana (yes, there are 46 hiragana characters, and you should learn them all ), then learn the 46 katakana, and gradually build up your kanji knowledge. Over time, you’ll see how hiragana vs katakana vs kanji are not in competition but work together to make written Japanese efficient, clear, and expressive. By understanding the differences and uses of each script, you’ll be well on your way to reading and writing Japanese with confidence.